Report: Damage caused by deep-seabed mining ‘extensive and irreversible’

A new report by wildlife conservation charity, Fauna & Flora, reveals growing evidence of the risks associated with deep-seabed mining, and concludes that its negative impacts are likely to be ‘extensive and irreversible’.

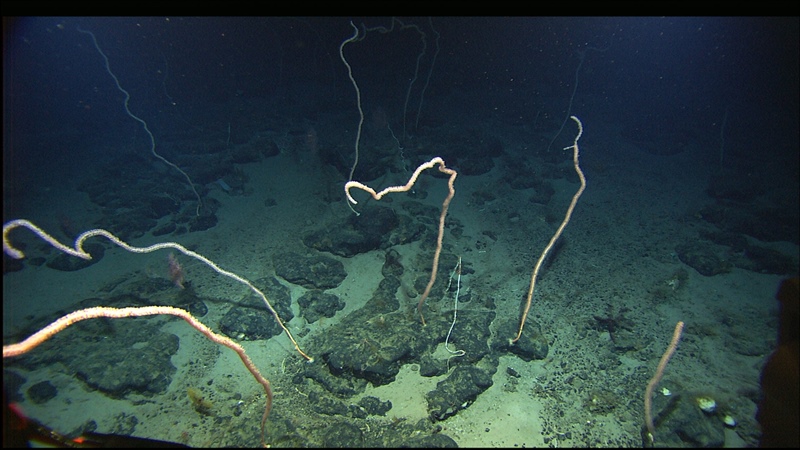

Deep-seabed mining is the proposed process of retrieving mineral deposits from the deep seabed. Despite widespread concern that it could severely damage marine biodiversity and ecosystems, there is a drive from some quarters to initiate deep-seabed mining, due to increasing demand for metals, such as lithium, copper and nickel, and depleting terrestrial resources.

In early 2020, Fauna & Flora published a report entitled ‘An assessment of the risks and impacts of seabed mining on marine ecosystems’ and raised its concerns about the threat deep-seabed mining posed to biodiversity, ecosystem function and dependent planetary systems. Since then, scientific attention on the issue has increased rapidly, with many new studies published on deep-sea environments, the functions and services they provide for humanity, and the potential implications of deep-seabed mining for marine life.

Fauna & Flora has now reviewed the new evidence to publish an update to its initial assessment. The analysis covers the many areas impacting the deep-seabed mining debate, including the sensitivity of deep-sea species and ecosystems to disturbance, the ability of the ocean floor to recover from mining impacts, the role of the ocean in regulating the climate, the societal implications of deep-sea mining risks and impacts, and the extent to which the anticipated impacts can be prevented, mitigated and managed.

The analysis demonstrates that deep-seabed mining will inevitably result in the loss of deep-sea biodiversity – with implications for associated ecosystem functions and services – and that, once lost, biodiversity will be impossible to restore. It also showcases compelling evidence that deep-seabed mining, through disturbance of marine sediment carbon stores and disruption of carbon cycling and storage processes, could contribute to the climate crisis.

Crucially, the report emphasises how little is still known about the diversity and complexity that exists in the deep sea, and the many new species that are yet to be discovered.

In the report summary, Fauna & Flora concludes that it remains premature for deep-seabed mining to proceed and, in the absence of any suitable, proven impact-avoidance or mitigation techniques, it should be avoided entirely.

“We know less about the deep sea than any other place on the planet; over 75 per cent of the seafloor still remains unmapped and less than one per cent of the deep ocean has been explored,” says Sophie Benbow, director of marine at Fauna & Flora. “What we do know, however, is that the ocean plays a critical role in the basic functioning of our planet and protecting its delicate ecosystem is, therefore, not just critical for marine biodiversity, but for all life of earth.

“The predicted consequences and huge uncertainties associated with deep-seabed mining must not be ignored. Bold decisions are now required to put ocean health and the benefits of the deep sea for all humankind front and centre. Once initiated, deep-seabed mining and its effects may be impossible to stop.”

Since 2020, the timeline for deep-seabed mining to transition from exploration to commercial exploitation has been accelerated. In June 2021, the Republic of Nauru notified the International Seabed Authority (ISA) – responsible for regulating mining in areas beyond national jurisdiction – of its intention to sponsor an exploitation application for polymetallic nodule mining in the Pacific. In doing so, Nauru triggered a ‘two-year rule’ – a legal provision which creates a countdown for the ISA to adopt its first set of exploitation regulations for deep-seabed mining and could result in the green light for deep-seabed mining in 2023.

However, a growing number of ISA member states are pushing against the pressure to be rushed into regulation and approval of mining contracts, and are calling for more time to develop a robust and science-based approach.

Catherine Weller, global policy director at Fauna & Flora, says: “This is a critical year for the future of our ocean. The newly agreed UN High Seas Treaty signifies a clear global recognition of the importance of ocean conservation, but collaborative efforts are still needed to keep the brakes on deep-seabed mining. In September 2021, members of the IUCN, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, voted to support a moratorium on deep-seabed mining unless and until a number of requirements are met. This included the stipulation that the risks of mining are comprehensively understood and effective protection can be ensured.

“The research analysed in Fauna & Flora’s update report unequivocally proves that this is still far from reality, and therefore we – alongside many other organisations working to protect the future of our planet – urge the ISA to avoid granting mining contracts prematurely and adopt a moratorium on deep-sea mining.”