Mission to investigate giant iceberg launches

A research mission to determine the impact of the giant A-68a iceberg on one of the world’s most important ecosystems gets underway next month. A team of scientists, led by British Antarctic Survey (BAS), will set sail on one of the National Oceanography Centre’s research ships bound for the sub-Antarctic island of South Georgia.

After satellite images revealed the giant iceberg’s trajectory towards South Georgia, the BAS science team put a proposal to NERC to fund an urgent mission south. The team will investigate the impact of freshwater ice melting into a region of the ocean that sustains colonies of penguins, seals and whales. These waters are also home to some of the most sustainably managed fisheries in the world.

Underwater robotic gliders will be deployed from the NOC research ship RRS James Cook, which will depart the Falkland Islands for the iceberg in late January.

Oceanographer Dr Povl Abrahamsen, from British Antarctic Survey, is leading the mission.

“We have a unique opportunity to visit the iceberg. Normally, it takes years to plan the logistics for marine research cruises, but NERC, working with the Government of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands and the UK Government’s Blue Belt Programme, recognised the urgency to act quickly, allowing us to study the iceberg during an upcoming voyage to monitor the ecosystem and climate of the Southern Ocean. Everyone is pulling out all the stops to make this happen,” he says.

The two 1.5m long untethered submersible gliders will spend almost four months collecting measurements of seawater salinity, temperature, and chlorophyll from opposite sides of the iceberg, piloted over satellite link by personnel at NOC and BAS. The team will also measure how much plankton is in the water and compare their findings with long-term oceanographic and wildlife studies around South Georgia and nearby Bird Island.

“Autonomous submarine gliders are an excellent, cost-effective, and sustainable means of gathering and recording important marine data,” says Steve Woodward, the NOC’s glider technical Lead. “In this case, we will program the NMEP gliders to get as close to the edge of the iceberg as we feel is safe and practicable, and collect the data that will be needed to enable the team to understand the implications of what is taking place with A-68a.”

Andrew Fleming, Head of Remote Sensing at BAS, has been tracking the iceberg’s journey on images from the Copernicus Sentinel-1 and other satellites. He says: “We are watching the progress of the A-68a iceberg very closely as we haven’t seen a berg of this size in the area for some time. As it breaks up, thousands of smaller icebergs have the possibility to obstruct shipping lanes in the area, especially as they disperse. The European Space Agency has delivered regular Sentinel-1 images and we will use these to continue tracking in the coming months.”

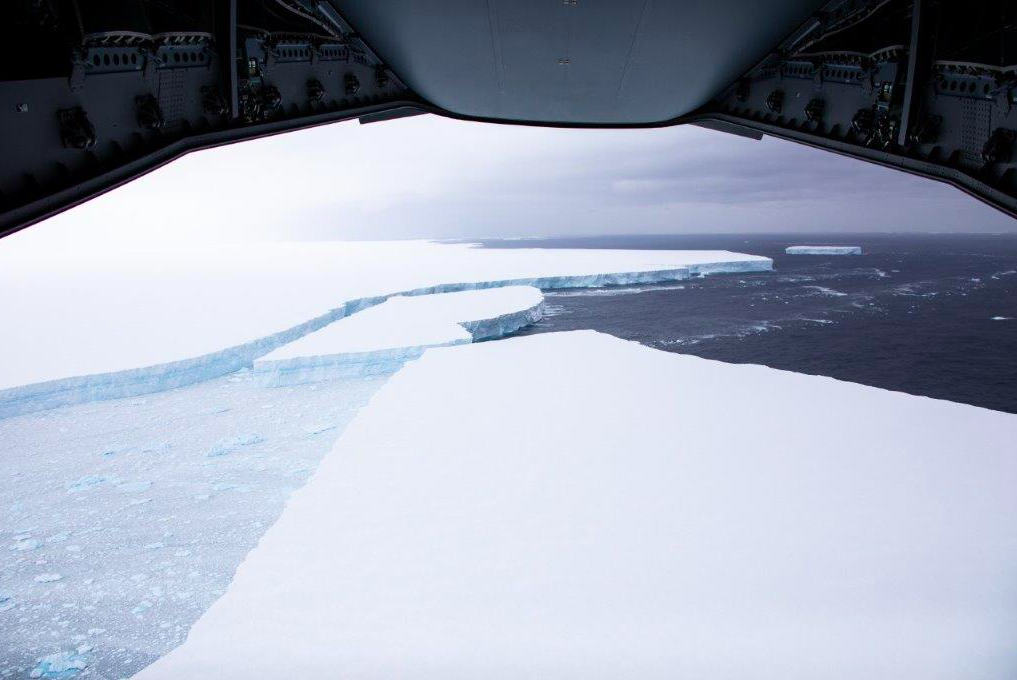

“The images and footage collected by MOD flight missions have helped enormously in confirming some of the features we can see in the images from space.”

The iceberg broke in two at the end of last week.

Strong currents took hold of it, causing it to shift direction and lose a major chunk of mass, a scientist said.

It pivoted nearly 180 degrees, according to Geraint Tarling, a biological oceanographer with the British Antarctic Survey.

“You can almost imagine it as a handbrake turn for the iceberg because the currents were so strong,” Tarling told The Guardian.

That was when the iceberg appeared to clip the shelf edge, and caused a large piece to break apart. That new piece is an iceberg in its own right and already has a name: A68D.

As of Friday, the original A68A iceberg was about 50km (31 miles) from the island’s west coast. It appeared, however, to be heading south-east towards another current that would probably carry it away from the shelf edge before sweeping it back around toward the island’s eastern shelf area.

The iceberg’s change of course could potentially still cause an environmental disaster along the island’s eastern coast, rather than the south-west, where it was initially thought to be headed.

“All of those things can still happen, nothing has changed in that regard,” says Tarling.