Calls for standardisation of floating buildings

As population growth puts pressure on urban space, some local authorities are building floating community structures. But the design and build of these innovative buildings poses a unique set of challenges, says Virginie Segura. She’s a project manager for Vicastel Project Management, based in Lyon (France), which is currently building a floating theatre in the city.

Firstly, says Segura, there is a lack of cohesive regulation and build standards. Depending on where clients are in the world, floating buildings are qualified differently. In the Netherlands they are considered houses, but in Singapore they are considered a boat and as such, must have an engine. In France, it varies from inland to coastal areas – if built on the interior waterways a floating building is considered a boat, if on seawater it is a house. In other places such as Hong Kong and some US states, it just isn’t allowed says Segura.

The confusion around the issue is underpinned by the recent ruling in Miami regarding a floating mansion. As reported in Marine Industry News, it will evade a tax bill of nearly $120,000 because its owners have proven it’s a boat.

“There is a lack of building regs in this area,” she says. “We need a roadmap, a standardised set of rules, for projects incorporating a floating building or structure. For example, on the inland waterways in France we use ES-TRIN 2021, the technical requirements in Europe when building vessels for use on interior waters – but this is related to boats and propulsion, not floating buildings which are anchored in place and don’t move.”

Secondly, the development of floating structures combines two very different professional disciplines, construction and naval architecture, which presents its own set of unique challenges.

“There are certainly challenges for construction companies when working with naval architects and marine experts within the ‘floating world’,” says Segura.

“The architects and builders do not have a fixed visual reference level to work from, which they would on land.

“We’re constantly asking them for the centre of gravity, considering the weight of their equipment and each component they’re installing inside the floating building. Environmental conditions also need to be taken in account, such as waves, water variation and current – things you just don’t need think about for a building on the land.

“From a project management perspective, to be able to propose a floating structure concept we need to first assess the global weight of the building, then look at the loads that building puts on the floating structure as this will affect its stability and floatability. This must be done at a conceptual level to be able to estimate the project in terms of price and complexity.

“Once the conception phase is complete, we have to ask for even more accuracy on the technical packages (electricity, plumbing, HVAC, cladding, plasterboard etc) which affect the weight of the building. It is at this point that we can complete a stability assessment based on ES-TRIN 2021 or NR580 to verify the stability criteria. Only when this is confirmed can we progress to construction. So, you can see, we require a huge amount of accurate information from a construction company before a project can be deemed feasible in a specific location. It’s a very different way of working.”

Anchoring systems

Thirdly, says Segura, an anchoring system is a vital element of any floating building project. There is no engine or anchor windlass and therefore it must be tethered in place by a secure mooring system which can weather the elements and environmental loads.

As the anchoring system will, in most cases, connect with the sea or riverbed, the effect on the marine ecosystem must also be considered, often requiring additional expertise which must be costed into the project at the start. Depending on the chosen system, it may also affect the aesthetics of the project and must be incorporated into the initial designs. But this doesn’t always happen.

“As it’s not usually a component of a building’s design, the anchoring system often initially gets overlooked by the architects and designers, but it can have a visual impact as well as technically be very challenging depending on the environmental conditions,” says Segura. “When experience on these types of projects is limited, the dimensioning of the anchoring system and thus the cost is often greatly underestimated. Specialist expertise in this area at the design phase is essential to deliver the project effectively and within budget.”

Finally, there is no blueprint or best practice guidance for development companies to work from, which would help meet and overcome the challenges which Segura outlines.

“Floating buildings will grow in popularity as population pressure requires governments to think outside the box,” she says.

“To ensure that these structures are safe and have longevity, we need a common standard for all to adopt. We need to work globally to reach this standard. We, at Vicastel Project Management, would be keen to liaise with other interested parties in creating these guidelines which can be applied worldwide.”

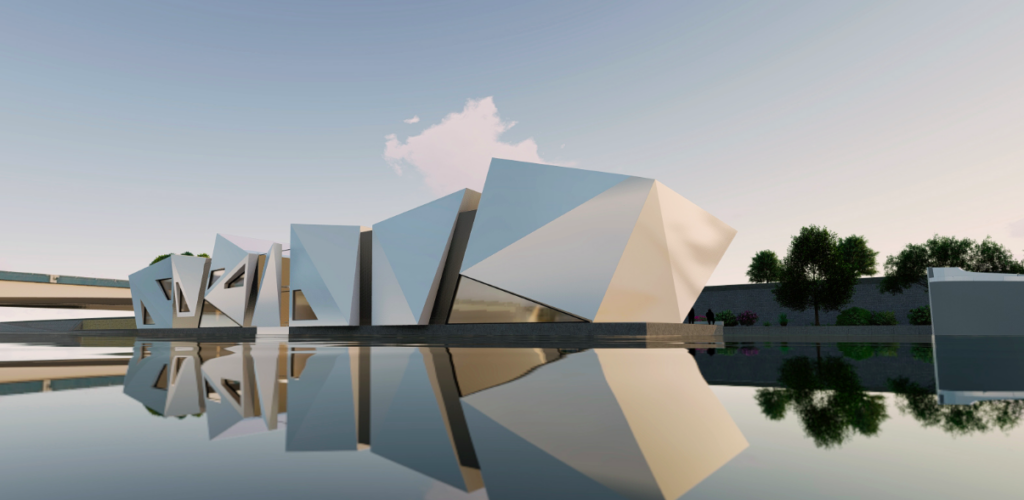

Segura’s company is currently working on two such projects in France. The first, a floating theatre in the city of Lyon called L’île ô, is made with a concrete hull, CLT structure and cladding. It’s set to open in October 2022.

Dedicated to promoting the fragility and care of the marine environment, the second project is Maison de la Mer which opens September 2022. Financed by the local town hall in Agde, South of France, this modern edifice is constructed on a concrete platform, created from concrete breakwater units more commonly used as wave attenuators at the entrance to harbours and marinas (supplied by Inland and Coastal Marina Systems which is exhibiting its workboat berthing solutions at Seawork).