Lessons learned from marine accidents

Published on April 1st, 2019: The Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) examines and investigates all types of marine accidents to or on board UK vessels worldwide, and other vessels in UK territorial waters.

Their distribution of MAIB Safety Digest 1/2019 provides a collection of lessons learned from marine accidents, drawing the attention of the marine community to some of the lessons arising from investigations into recent accidents and incidents.

The Safety Digest is a 70 page document of countless mistakes, and while most do not pertain directly to yacht racing, we found Case 24 to describe an incident during the Clipper 2017-18 Round the World Yacht Race.

The third leg of the race began on October 31 and was to unleash the 12 teams into the harsh conditions of the Southern Ocean course from Cape Town, South Africa to Fremantle, Australia.

However, one team didn’t survive the first day when just hours after the start, they ran aground along the western side of Cape Peninsula, an offshore reef at Olifantsbospunt between Cape Town and Cape Point.

Here are the MAIB findings:

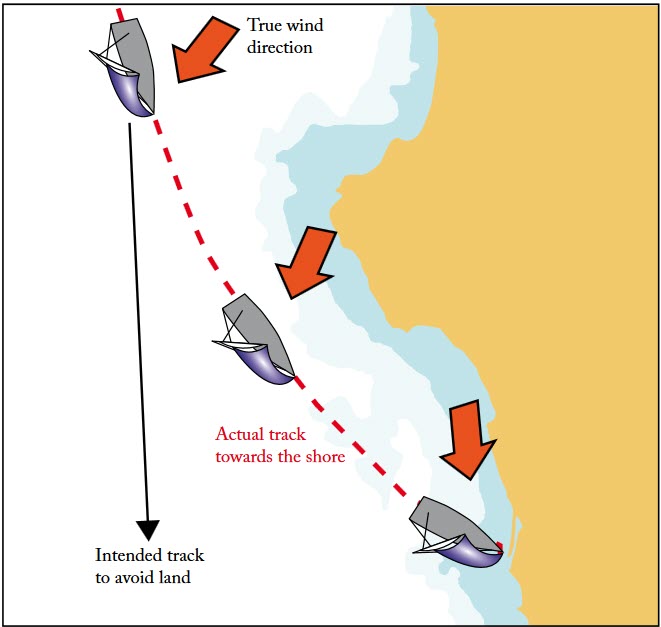

Figure 1: The intended and actual tracks of the yacht

The Narrative:

A large commercially operated yacht was taking part in an ocean race. There was a professional skipper in charge and the rest of the crew were amateur sailors, some of whom had previous sailing experience. The following accident happened on the first day of the race.

After the start, the fleet of yachts headed out to sea but needed to pass a headland before commencing the ocean crossing. After dark, one of the yachts was sailing downwind with its mainsail and a spinnaker hoisted. The yacht was on a heading that would take it safely past the headland and into the open sea.

However, over about an hour, the true wind backed by around 70 degrees. To maintain the same relative wind direction and prevent a potentially dangerous accidental gybe, the crew made a succession of small alterations of course to port. These course changes had the effect of driving the yacht unintentionally close inshore (Figure 1).

The skipper had been monitoring the situation and realized that the yacht needed to be turned away from danger. However, soon after this turn was made, the yacht grounded and could not be freed. There was a delay of nearly an hour in alerting the coastguard; however, once they had been alerted, all the yacht’s crew were rescued into lifeboats. The yacht could not be salvaged and was cut up on the beach where it had grounded (Figure 2).

The Lessons

1. Every vessel, whatever its size or purpose, needs a passage plan that has identified all potential hazards for the voyage ahead. In this case, the skipper had intended to head away from land after the race start so was not planning to sail close to the shore. This meant that there was little expectation of having to manage coastal navigation. Nevertheless, the requirement to pass the headland meant that the passage plan should have assessed the risks of operating in shallow water.

2. When things start to go wrong on a yacht when inshore, safe navigation must remain a high priority. The skipper was the only person closely monitoring the navigation. Unfortunately, when the situation started to deteriorate, the skipper was required to be on deck to supervise the crew handling and turning the yacht. This meant that no-one was monitoring the plotter at the navigation station down below, and there was no plotter on deck. As a result, no-one understood the immediate risk of grounding. It was also unhelpful that it was dark and hazy with an unlit foreshore, which meant that there were few visual clues to the close proximity to land.

3. When properly set up, alarms can provide vital warning of danger. There were no navigational alarms set on the yacht; the electronic navigation system did not have safety depths set and, although the echo sounder was running, the audible shallow water alarm was turned off. The yacht was well-equipped with a suite of capable modern electronic safety equipment that could have helped to warn the crew of danger ahead.

4. Any vessel in a distress situation should call for assistance as soon as possible. In this accident, the crew did not make an immediate “Mayday” or “Pan Pan” emergency call on VHF radio. Had this been done, it is highly likely that the local coastguard would have heard the call immediately and the crew could have been rescued earlier.