Nearly all marine species ‘face extinction risk by end of century’ unless emissions are curbed

Coral bleaching on Heron Island, Great Barrier Reef, 2015

Credit: The Ocean Agency / Ocean Image Bank

Coral bleaching on Heron Island, Great Barrier Reef, 2015

Credit: The Ocean Agency / Ocean Image Bank

A new study has laid out the alarming impact that climate change will have on marine ecosystems by the end of the 21st century, if greenhouse gas emissions are not curbed.

A study published in Nature Climate Change on Monday (22 Aug 22) examines how marine species will react to different emissions scenarios detailed by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

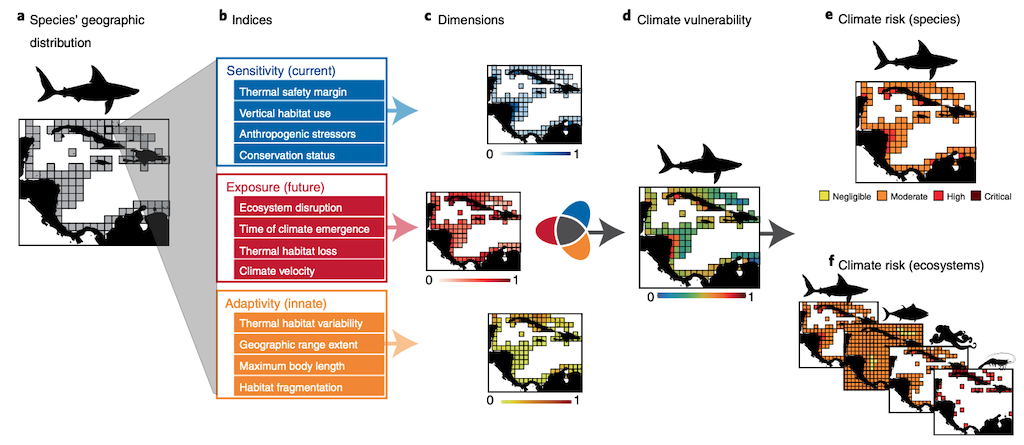

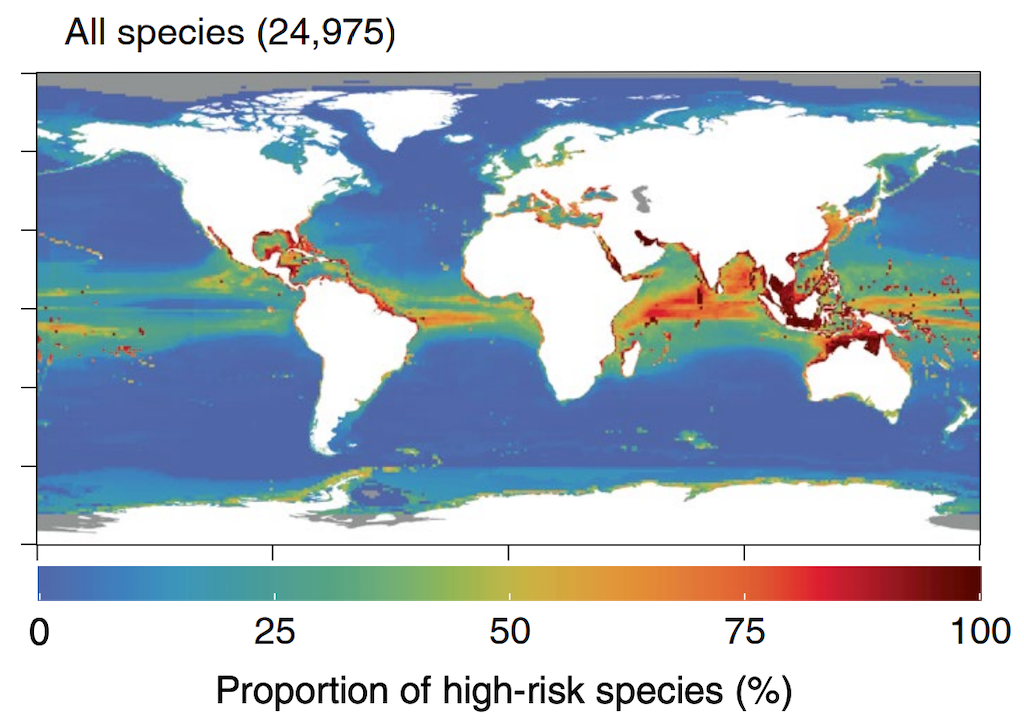

The authors have devised a new index – the Climate Risk Index for Biodiversity (CRIB) – that assesses the climate risk for nearly 25,000 marine species and their ecosystems.

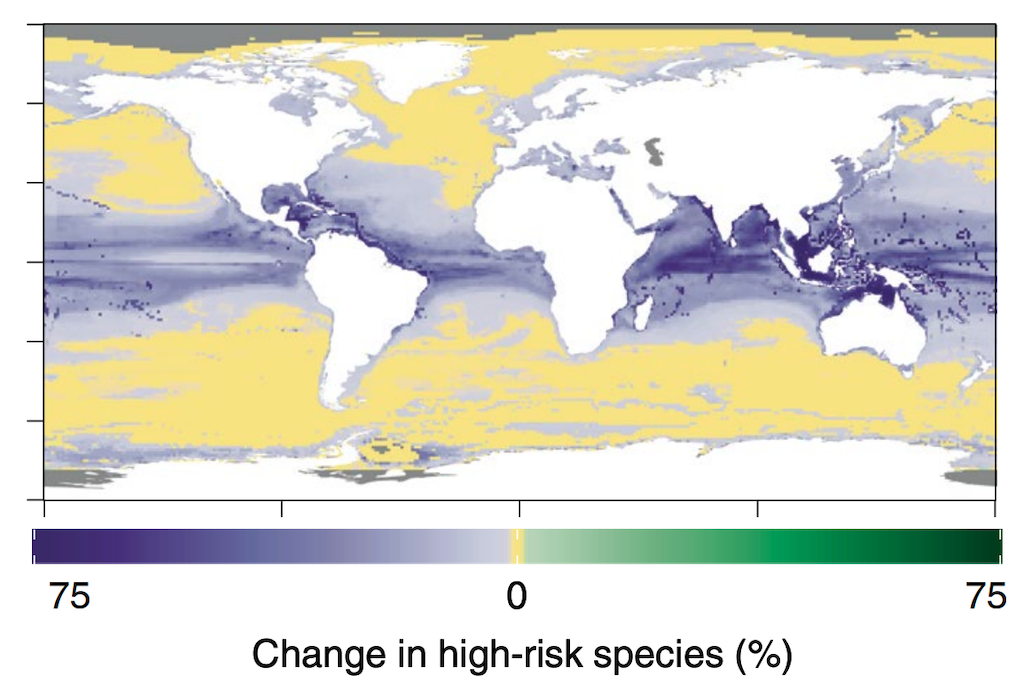

The findings show that, under very high emissions, almost 90 per cent of these 25,000 species are put at high or critical risk, with species at risk across 85 per cent of their native areas, on average.

However, in an emissions mitigation scenario consistent with the 2C global warming limit in the Paris Agreement, the risk is reduced for virtually all marine species and ecosystems.

In a guest post for Carbon Brief, study authors Dr Daniel Boyce and Dr Derek Tittensor say that “climate change is rewiring marine ecosystems at an alarming rate”. They explain that their work essentially created a “climate report card” for marine life that tells us “which will be winners or losers under climate change.”

The framework is based on an analysis of how the innate characteristics of a species – such as body size and temperature tolerance – interact with past, present, and future climate conditions.

“Just as a report card grades students on subjects such as maths and science, we used a data-driven approach to score individual species on 12 specific climate risk factors in all parts of the ocean where they live,” the authors say.

Under the highest emissions scenario, called SSP5-8.5, current carbon dioxide emissions will have doubled by 2050.

Under this scenario, the world will be up to 5.7C warmer by 2100 than in pre-industrial times. The study finds that, in this scenario, about 90 per cent of marine life in the upper 100 meters of the ocean would be at high or critical risk of extinction.

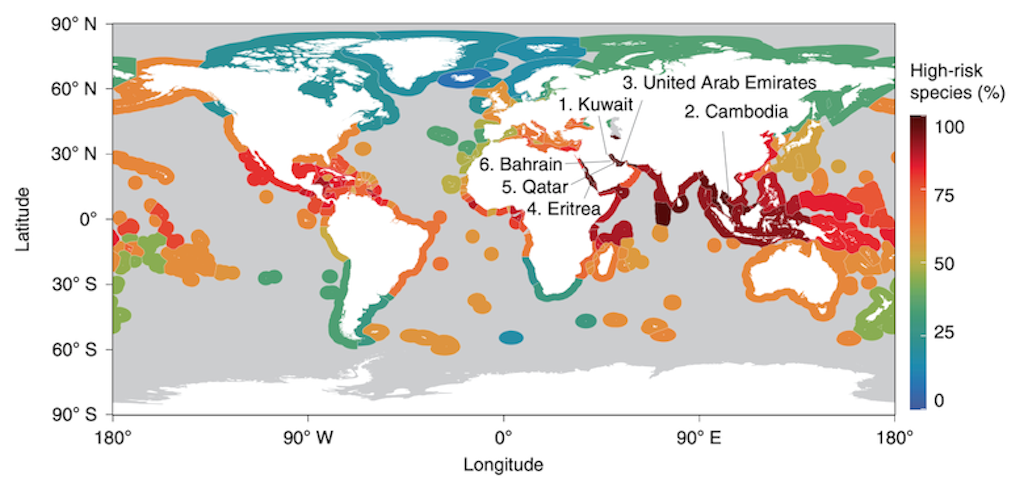

Risks are found to be higher in locations with larger numbers of species assessed as having higher extinction risk. Endemic species, which are only found in one geographic area and are inherently more vulnerable.

The authors find that there could be severe knock-on impacts for people who rely on the ocean most.

“Under the high emissions scenario, climate risks for species fished by humans for food or revenue – such as, for instance, cod, anchovies and lobsters – were systematically greater within the territories of low-income nations,” they say.

Authors point out that such low-income countries typically rely more on fisheries to meet their population’s nutritional needs. While low-income countries have made the smallest contribution to climate change, they are likely to bear the brunt of the impacts while being the least well positioned to adapt — an example of climate inequality.

On the other hand, if the world implements serious cuts and reaches net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, limiting global warming to 2C, “virtually all species” the researchers examined would have their risk of extinction drastically reduced.

The authors say this low emissions scenario would “have substantial benefits for marine life, with the disproportionate climate risk for ecosystem structure, biodiversity hotspots, fisheries and low-income nations being greatly reduced or eliminated.”

It would also be hugely beneficial for food-insecure nations, researchers add.

“Overall, our results indicate that the climate risk for marine life is strongly dependent on the magnitude of future emissions,” researchers concluded.

Climate scientists including Boyce and Tittensor have shown the planet could be 3.5C warmer within 80 years if countries don’t substantially increase their efforts to reduce emissions. The ‘worst case’ scenario in this report is therefore possible.

“The reality is that climate change is already impacting the oceans, and even with effective climate mitigation, they will continue to change,” they write in the guest blog post. “Therefore, adapting to a warming climate is crucial to building resilience for both ocean species and people.”

In July, MIN reported that plankton, the tiny organisms that sustain life in the seas, has all but been wiped out in the equatorial Atlantic. The team’s spent two years collecting water samples from the equatorial Atlantic and in a dire warning says this means the equatorial Atlantic is ‘pretty much dead’.