Ocean CleanUp’s cleanup is better for environment than leaving plastic to fester

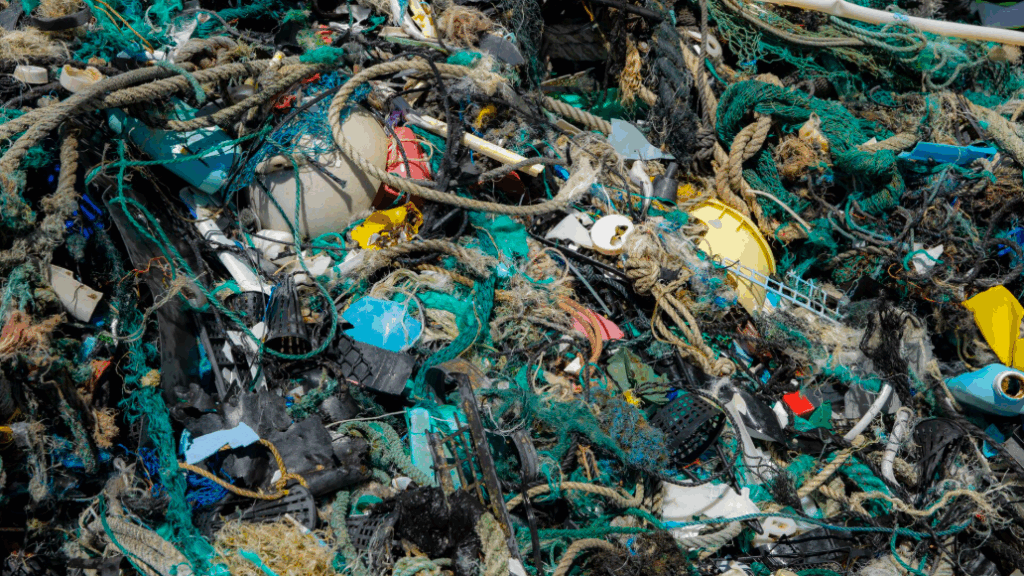

“Marine life is more vulnerable to plastic pollution than to our offshore cleanup efforts in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP),” declares Dr. Matthias Egger, the Ocean CleanUp’s director of environmental and social affairs. He’s been evaluating the environmental impact of cleaning up the GPGP which is estimated to contain around 100,000 tons of plastic. The ‘patch’ roughly covers an area three times the size of France and is located between California and Hawaii. It is comprised of ghost nets and other fishing gear, complimented by a wide array of plastic pieces dating back to the 1960s.

With global plastic production set to double by 2050, the problem of the GPGP requires systemic change and having robust policies in place, such as the proposed Global Plastics Treaty and business, consumer and fishing industry changes.

But while the Ocean CleanUp is busily trying to decrease plastic within the oceans, it has found itself having to assess what it does – in terms of environmental cost – against what it delivers, now and into the future.

“The estimated cleanup-related carbon emissions are significantly lower than mitigated potential long-term microplastics impacts on ocean carbon sequestration, which is a critical element in regulating our climate and absorbing up to 30 per cent of man-made CO2 emissions,” Egger says. He’s confident in this after undertaking a Net Environmental Benefit Assessment.

“This assessment demonstrates that it is possible to carry out such an innovative feat of human ingenuity to clean the ocean in not only an environmentally friendly way but with a benefit to ecosystems and climate regulation that can be replicated in other areas using the framework we have developed.”

In the study, published in science journal Scientific Reports, scientists found that the benefits of the removal of the GPGP outweigh the potential environmental costs, including greenhouse gas emissions and ecosystem disruptions, as a result of carrying out the cleanup.

The assessment was led by the Ocean CleanUp (a Dutch-based nonprofit). It has been using two vessels to tow a 2.2km wide collection system to capture the floating plastic over the past years.

The study’s release comes ahead of the Third United Nations Ocean Conference (UNOC3) in Nice, France, in June and this summer’s Global Plastics Treaty debate in Geneva. The latter will be crucial in addressing global plastic pollution on land, and the environmentally sound removal of legacy ocean plastic. This is central to The Ocean CleanUp’s mission.

The peer-reviewed assessment was commissioned by The Ocean CleanUp and co-authored by 15 independent scientists to ensure impartiality. The organisation now says the created framework can also act as a template to ascertain the net environmental benefits of cleaning up other areas of ocean.

Fisheries are highlighted as the main contributor to floating marine litter in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, says Dr. Vilma Havas, study co-author and independent scientist. “Increased focus is needed to limit the influx of discarded gear through cross-sectoral cooperation and holistic, long-term policies that support sustainable fisheries. Gear losses can effectively be targeted through life cycle-focused policies that apply circularity principles, such as Extended Producer Responsibility schemes that promote increased transparency of material flows in fisheries.”

The review is also a response to concerns raised about bycatch of marine life from the cleanup operations, which the study found to be minimal, and previous issues raised on the impact on species living amongst the plastic waste. Most species were found to be ‘coastal invaders’ that had hitched a ride on the plastic and their removal could restore the balance of the ecosystem.

Microplastics interfere with natural processes

As the ocean plastic decomposes and fragments into microplastics, it releases greenhouse gases which contribute to climate change. Microplastics also disrupt the ocean’s natural carbon cycle or ‘biological pump’ which is a natural process that helps absorb carbon from the atmosphere which is then stored in the deeper ocean and is crucial to regulate the earth’s climate.

Microplastics interfere with the process by which zooplankton and other microscopic creatures feed on carbon rich particles then sink towards the ocean floor, naturally sequestering the carbon.

Ocean CleanUp deployed its first Interceptor river cleanup solution in the Chao Phraya River, Bangkok – part of a wider partnership to tackle plastic pollution leaking from one the world’s busiest working rivers – in April 2024. It also livestreamed its 100th extraction of garbage from the GPGP later that year.